In my previous blog post, I had highlighted the burden of personnel costs—65% of the defense budget—strangling India’s military modernization India’s Defense Dilemma: The High Cost of Staying Behind in the Fifth-Generation Jet Race. But that’s not the only problem that has kept the Indian defense industry restrained. In this post, I uncover another reason that makes us still think about foreign imports: a toxic mix of brain drain, import addiction, and 26 lost years that have left us dreaming of F-35s and Su-57s while our own fighter jet ambitions flounder. Bengaluru, the heart of India’s defense industry, must face this ugly truth and demand better—or we’ll be grounded for another generation.

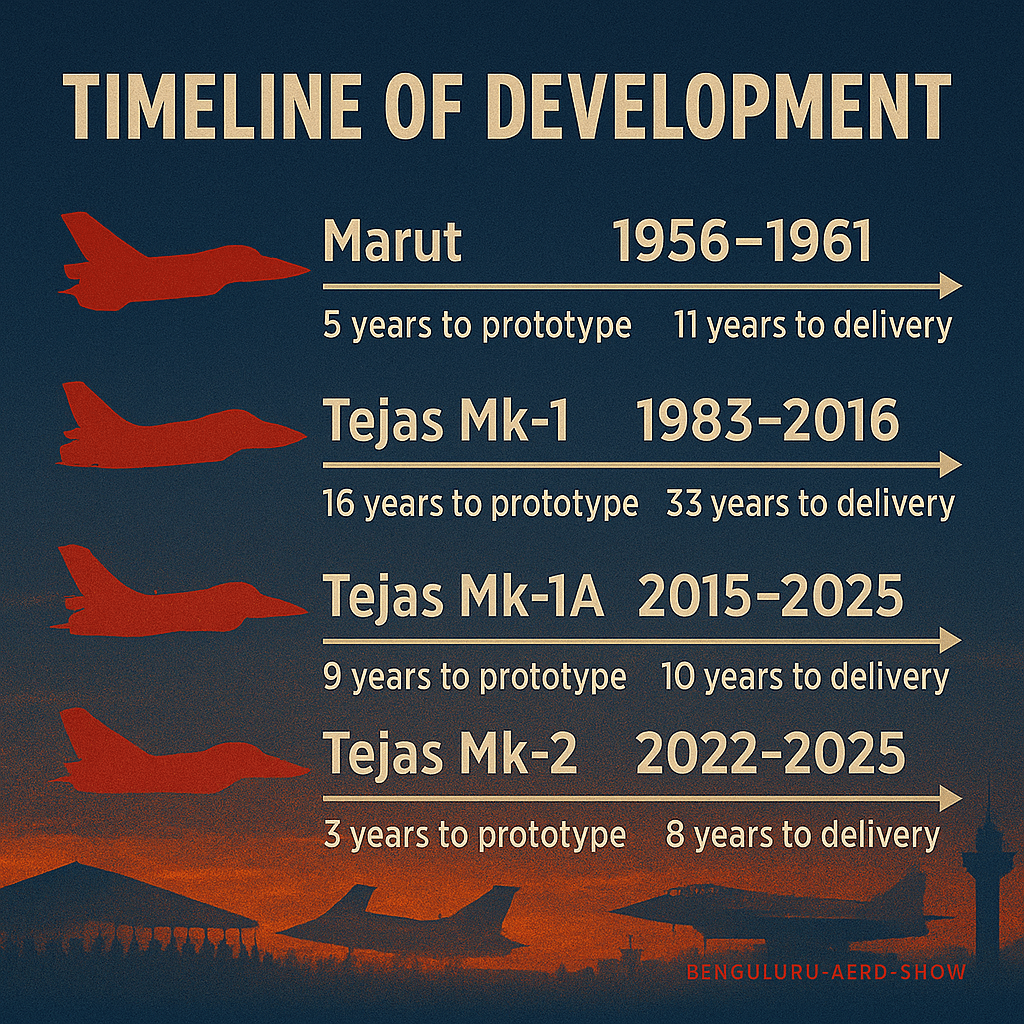

India’s first indigenous jet fighter, the HAL HF-24 Marut, started with promise. Launched in 1956 under Kurt Tank at HAL Bengaluru, its prototype flew on June 17, 1961—just 5 years later. By April 1, 1967, the first Marut reached the Indian Air Force (IAF)—11 years from start to delivery. It flew 200+ ground attack sorties in the 1971 Indo-Pakistan War, even scoring a rare air kill against a PAF F-86 Sabre. But Marut had a problem. Designed for Mach 2, it limped to Mach 0.95, crippled by underpowered Bristol Siddeley Orpheus engines (21.6 kN thrust each). By 1990, after producing 147 jets, it was scrapped—replaced by imported Jaguars and MiG-23s. India failed to build on this early success, betraying its own potential.

Post-Marut, India’s government turned its back on indigenous fighter jets for 26 years—until 1983. Instead, we became an import junkie, guzzling Soviet aircraft through the 1971 Indo-Soviet Treaty: 874 MiG-21s by 1983 (₹50 lakh/unit), Jaguars in 1979 (₹1,200 crore), and MiG-23s in 1981. This cowardice left the IAF at 30 squadrons by 1990, far below the required 42.5, while HAL’s talent bled out. Over 200 engineers fled to the U.S. and Europe in the 1970s, their Marut-honed skills wasted abroad because India offered them nothing. A new fighter project would have needed 500-1,000 engineers—HAL had nowhere near that after the exodus.

Meanwhile, other sectors like space and nuclear got a better treatment. ISRO, for example, trained thousands by 1980, launching SLV-3 that year. The nuclear program, with 5,000 scientists at BARC, delivered Pokhran-I in 1974. Why did aerospace get shafted? Because our leaders lacked the spine to invest in long-term self-reliance, preferring quick fixes over building a future. This betrayal set India back decades, forcing us to play catch-up while rivals like China built J-20s.

The Tejas program, launched in 1983 amid Pakistan’s F-16 acquisitions, was meant to replace MiG-21s. Instead, it became a monument to incompetence. The first prototype flew on January 4, 2001—16 years later—and deliveries didn’t start until July 1, 2016—33 years after sanction. The IAF ordered 40 Tejas Mk-1 jets, with 38 delivered by May 2025, barely equipping two squadrons.

Why the glacial pace? The 26-year gap since Marut meant we had to rebuild skills from scratch—a damning indictment of our failure to nurture talent. Adding to this was that the plan was to build a complex fourth generation fighter jet. It meant, the engineers were asked to sprint, when they were not allowed a room to crawl and walk. The 33 years taken to reach the delivery was possibly the slowest in the entire world.

Sanctioned in 2015, the Tejas Mk-1A showed improvement. Its first production-series prototype flew on March 28, 2024—9 years later—with deliveries set for November 2025, totaling 10 years. The IAF ordered 83 Mk-1A jets in 2021 (₹48,000 crore), with 97 more under negotiation (₹67,000 crore), potentially totaling 180 jets. With 43 upgrades like self-protection jammers and radar for detecting targets, it’s a step up, aiming for 60-70% indigenous content by 2029.

The timeline drop from 33 years to 10 years shows what sustained skills can do. Tejas Mk-1 trained 3,000 professionals at HAL and ADA, building expertise in composites and avionics. But delays in GE F404 engine supplies pushed deliveries from 2024 to late 2025, exposing our engine dependency. Had we built on the Marut, we could have had a 4th-gen fighter by the 1980s, not 2016. Instead, we’re still begging for foreign engines while China fields 5th-gen J-20s, inducted in just 10 years (2006-2016). India’s 33-year crawl for Tejas Mk-1 is a global embarrassment.

Sanctioned on September 1, 2022, the Tejas Mk-2 aims for a prototype roll-out by late 2025 and first flight in early 2026—just 3 years from sanction. Over 60% of the prototype was complete by early 2025, with induction targeted for 2028-29 (8 years total). This 4.5-gen fighter, with 82-90% indigenous content, could replace Mirage-2000s and MiG-29s, with the IAF eyeing 108 jets (potentially 210).

This pace is impressive, probably the fastest in the entire world. But we’re still tethered to GE F414 engines, and HAL’s history of delays (e.g., Mk-1A) casts a shadow. Continuous development since 1983 is paying off, but one misstep could unravel it all. India cannot afford another Congress lead Center for at least a decade.

The 2016 Rafale deal for 36 jets (₹59,000 crore, ~$8 billion) mandated a 50% offset—$3.95 billion (₹30,000 crore) injected into India’s defense sector—offering a lifeline to build the industrial ecosystem we’ve long lacked, despite fierce opposition from Congress and Rahul Gandhi, who tried to bury the deal with relentless smear campaigns. This boost has ignited a transformative public-private partnership, with over 250 SMEs stepping up as the backbone of India’s defense ambitions.

Companies like Alpha Tocol, which delivered a rear fuselage for Tejas Mk-1A in March 2025, and giants like L&T, Tata Advanced Systems, and VEM Technologies, producing wings, fuselages, and avionics, are driving innovation and self-reliance. Their efforts, backed by the Rafale offset, enabled the Nashik facility—built entirely with these funds in collaboration with Dassault—to roll out its first Mk-1A on May 8, 2025, scaling production to 16-24 jets annually by FY 2025-26 (up from 8 in FY 2024-25). The offset has further empowered this ecosystem, spanning Bengaluru to Nashik, by upskilling 2,000 engineers since 2018 and transferring tech like Thales’ RBE2 radar, enhancing Tejas’s Uttam AESA system. This synergy is creating thousands of jobs across Bengaluru, Pune, and Hyderabad, building a supply chain that’s laying the foundation for self-reliance. With this ecosystem and public-private partnership, HAL’s capacity constraints are no longer a bottleneck, signaling a path to self-reliance—though it may still take a decade to fully realize.

The IAF limps along at 31 squadrons in 2025, against a required 42.5, facing China’s J-20s with Rafales and delayed Tejas jets. The 26-year gap post-Marut gutted our skills, forcing a 33-year slog for Tejas Mk-1. Now, with timelines shrinking to 3 years for Mk-2, sustained skills show promise—but it’s not enough. India can’t afford more lost decades like 1960s to 1980s or 2004 to 2014. We need:

- Continuous Projects: No more gaps—AMCA (2035) must be accelerated. We can’t risk UPA-like governments derailing progress until then.

- Skill Retention: Stop brain drain with incentives, like ISRO did.

- R&D Investment: Increase the defense budget, but prioritize R&D over personnel costs.

- Private Participation: Empower private players to lead, not languish under HAL’s shadow.

Thanks for reading! I hope you liked and enjoyed the article, if you did, please subscribe to the blog, I still am writing on the next part of the same topic.

Also read:

Leave a comment